Antisemitism in the Administration of the Men's Penitentiary at the Ljubljana Castle

Ljubljana, Graz, March 18-June 3, 1887

Original, manuscript, 4 documents, 8 pages

Reference code: SI AS 351, Državno tožilstvo v Ljubljani, technical unit SI AS 351/1/5/2/1 and SI AS 351/1/5/2/4

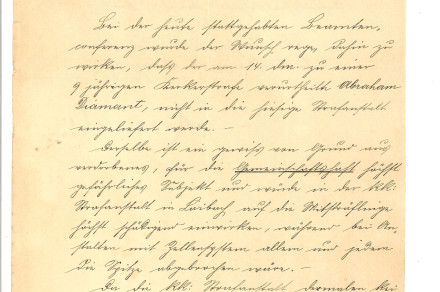

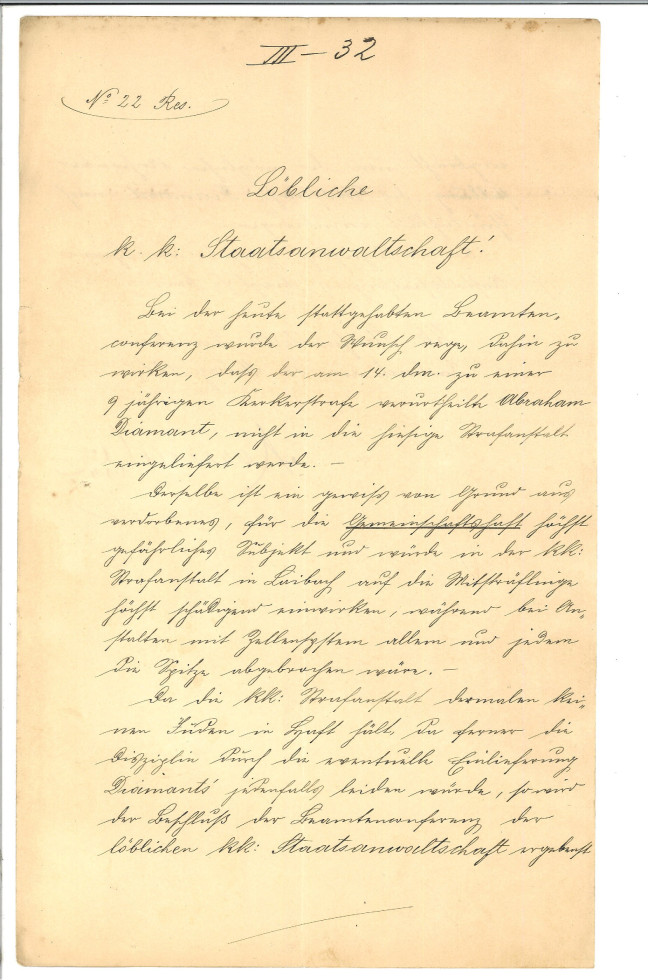

Director of the Men’s Penitentiary at the Ljubljana Castle, Markovič addressing his letter to the State Prosecutor’s Office in Ljubljana, expressing his wish that the convicted Abraham Diamant did not serve his sentence in his prisson. | Author Arhiv Republike Slovenije

In the closing decades of the 19th century, there was a noticeable rise in antisemitism sweeping across Europe and in Slovenian lands as well. In addition to long-standing religion-based accusations that had been used against them ever since the Middle Ages, Jews were now also being blamed for the negative effects of capitalism, such as usury, the collapse of small farmers and craftsmen, the devastating consequences of the Vienna stock market crash in 1873, and so on. Public opinion was rife with prejudice against Jews, which was vividly reflected in the negative newspaper reporting. Antisemitism was deeply embedded in all layers of the Slovenian society, regardless of the differences in ideology or class, and it was present in the Austrian state administration as well, as evidenced by the records preserved in the fonds of the State Prosecutor’s Office in Ljubljana.

A jury trial against Abraham Diamant before the Ljubljana Provincial Court, which took place in mid-March 1887, sparked a lot of public interest. According to the newspaper Slovenski narod, the courtroom was packed, and since Diamant was a servant of a well-known rich noblewoman Gariboldi, the crowd witnessing the trial included “many ladies and aristocrats”, all of them “hoping to hear some spicy details”. The journalist reporting on the trial saw Abraham Diamant as “… a true example of Jews that were known as “Krättzer”, arrogant in his behaviour, and giving impression of a cunning impostor, a highly dangerous and extremely odious person”.

The defendant was a 32-year-old Hungarian Jew. He finished the third year of grammar school, and in the course of his career tried his hand at being a merchant, waiter, agent, pedlar, and finally a servant. He had several prior convictions for theft, and his photo was included in the albums of criminals kept by the Viennese and Pest police force. Diamant was accused of stealing jewellery, money and securities worth a total of 46,533 Gulden and 90 Kreutzer from the drawer of his employer Katarina von Gariboldi on January 17, 1887. The list of stolen goods included 33 items and took up almost half of a newspaper column. He carried out the theft after having heard that Gariboldi was planning to fire him the following day for being lazy, sloppy and unable to serve properly. The fugitive Diamant was apprehended the very next day, on January 18, at Pragarsko, together with most of the stolen goods. The journalist for the Slovenski narod did not forget to point out that Gariboldi employed Diamant on the recommendation of Franz Müller, the editor of the German liberal newspaper Laibacher Wochenblatt. Namely, Slovenians tended to associate German liberal constitutionalist politicians with the Jews. Already in 1878, for example, when Filip Haderlap, the editor of the newspaper Slovenec, was a defendant in a court procedure before the jury court in Ljubljana, he stated: Constitutional members of the parliament took care of themselves and together with the Jews established all sorts of banks and companies, which one could only describe as plundering … the Jews live off the high interests paid to them by the state through the taxes … all supply contracts are made with the Jews who only look after their own interests.”

During the trial, Diamant was bold and impudent. When detained in custody before the trial, he pretended to be crazy, he faked epileptic fits and even simulated an attempted suicide to try and convince the authorities to send him to Studenec asylum instead of jail. His defence was also rather bizarre; he claimed to have committed the theft because he had been offended and drunk: “I took everything because Mrs. von Gariboldi mistreated me and refused to take me to the theatre with her, which she had promised to do … She has brought all of this on herself. She gives nothing to nobody. If a beggar comes to the house, she says:”Checosa è questa roba?” and chases him away. But he personally believes that she has enough money and that there is no harm in taking some away from her.”

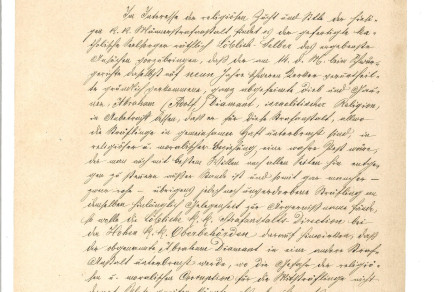

When the jury found him guilty and sentenced him to nine years of prison with hard labour and fasting once a month, Diamant was supposed to start his sentence at the Men’s Penitentiary at the Ljubljana Castle. But here things became complicated. The prison priest Janez Tomažič firmly opposed Diamant serving his sentence at the Ljubljana Castle and on March 18, 1887, he sent the following letter to the penitentiary’s administration: “In the interest of religious education and the habits developed at this penitentiary, the undersigned Catholic pastor is hereby submitting the following request. On the 14th of this month, Abraham Diamant, a completely degenerate and cunning thief and swindler of Israelite faith, was sentenced by the jury court to nine years of prison with hard labour. Considering that inmates at this penitentiary serve their sentences together, from religious and moral standpoint Diamant would be a real plague.”

The pastor continued by saying that the corrupting influence of the fallen Diamant on the rest of the prisoners, who “are rough but not yet corrupt” would be devastating and could not be prevented despite all the efforts to do so. He therefore asked that Diamant be sent to serve his sentence in another penitentiary, where the danger of his religious and moral corruption for fellow inmates would be lesser than at the Ljubljana Castle. It is not clear how the thief Diamant could morally corrupt other inmates, among whom one could find a diversity of criminals – murderers, rapists, arsonists, cheats, money forgers, etc. It is also hard to understand how a Jewish criminal could influence Catholic prisoners in the sense of “religious corruption”. During the 19th and 20th centuries there were several conversions from Jewish to Catholic or Protestant faith, but no recorder instances of conversions in the opposite direction. It seems that Diamant was troublesome solely because he was a Jew. This can also be concluded from the letter written by Markovič (Marcovich), director of the Ljubljana Men’s Penitentiary, and addressed to the State Prosecutor’s Office in Ljubljana. In his letter, to which he enclosed the request of pastor Tomažič written on the same day, he asked the State Prosecutor’s Office not to send Diamant to the Ljubljana penitentiary, a decision that was agreed upon by all penitentiary officials. At the Ljubljana Castle penitentiary Diamant would pose a great threat, whereas the risk would be much smaller if he served his sentence in penitentiaries that are divided into cells, where inmates had little interaction with each other. In his letter Markovič also explicitly stated that at that time there were no Jews serving sentences in the Men’s Penitentiary at the Ljubljana Castle!

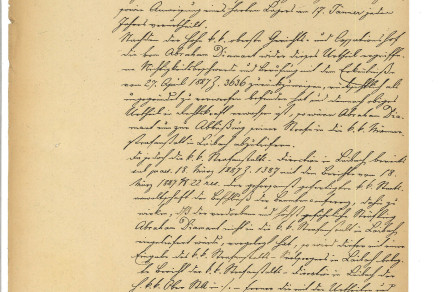

The humble request, initiated by pastor Tomažič and supported by director Markovič, then in a typical Austrian bureaucracy manner roamed onwards and upwards the Austrian bureaucratic pyramid. On May 23, 1887, the Ljubljana State Prosecutor Perše (Persche) addressed a letter to the Higher State Prosecutor’s Office in Graz, explaining that on April 27, 1887, the Supreme Court in Vienna dismissed Abraham Diamant’s complaint for annulment, thus making the judgement final and ordering him to start serving his sentence at the Men’s Penitentiary at the Ljubljana Castle. However, Perše also took the view that Diamant should be sent to another penitentiary, since he was considered to be a dangerous criminal, who had been constantly feigning madness and considering his escape while at prison in Ljubljana. On top of that, there were no other Israeli currently at the Ljubljana Castle penitentiary.

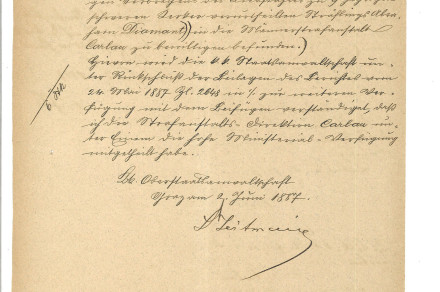

On June 2, 1887, the Higher State Prosecutor’s Office notified Perše that the Ministry of Justice approved that Abraham Diamant could start serving his sentence in the men’s penitentiary Carlau in Graz. Preparations for Diamant’s transfer to Graz began the very next day.

Dragan Matić

- Slovenski narod, 14. in 15. 3. 1887, »Tat žid Diamant pred porotniki«.

- Cankar, Tadej: »Odločnejši Protivniki semitstva«. O antisemitizimu in slovenskih liberalcih na Kranjskem. Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, Arhiv RS, 2023, pp. 76–125.

- Matić, Dragan: Tiskovna svoboda v krempljih ljubljanske justice. Zaplembe časopisov in druge tiskovne zadeve v obdobjih 1873−1889 in 1908−1914 v pravosodnih fondih Arhiva Republike Slovenije. Ljubljana: Arhiv RS, 2023, pp. 58–70.

- Štepec, Marko: Slovenski antisemitizem 1861−1895. MA thesis. Ljubljana, 1994, pp. 176 –177.