On the Expulsion of Wilhelm Palz from Ljubljana

Ljubljana, 1922-1928

Original: manuscript and typescript, Slovene, Serbo-Croatian, German language; 8 documents

Reference code: SI AS 68, Kraljevska banska uprava Dravske banovine, Upravni oddelek, šk. 7–4 1924, spis št. 15919/24

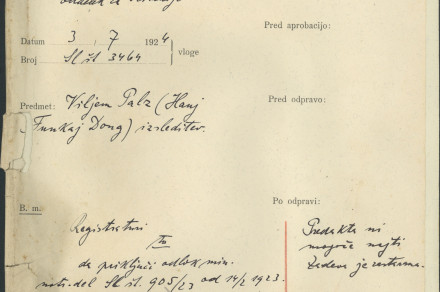

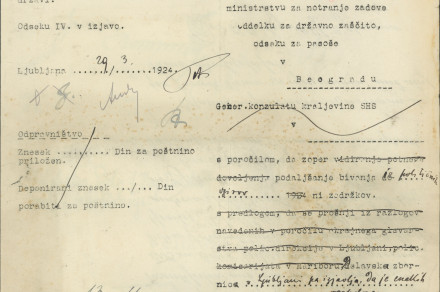

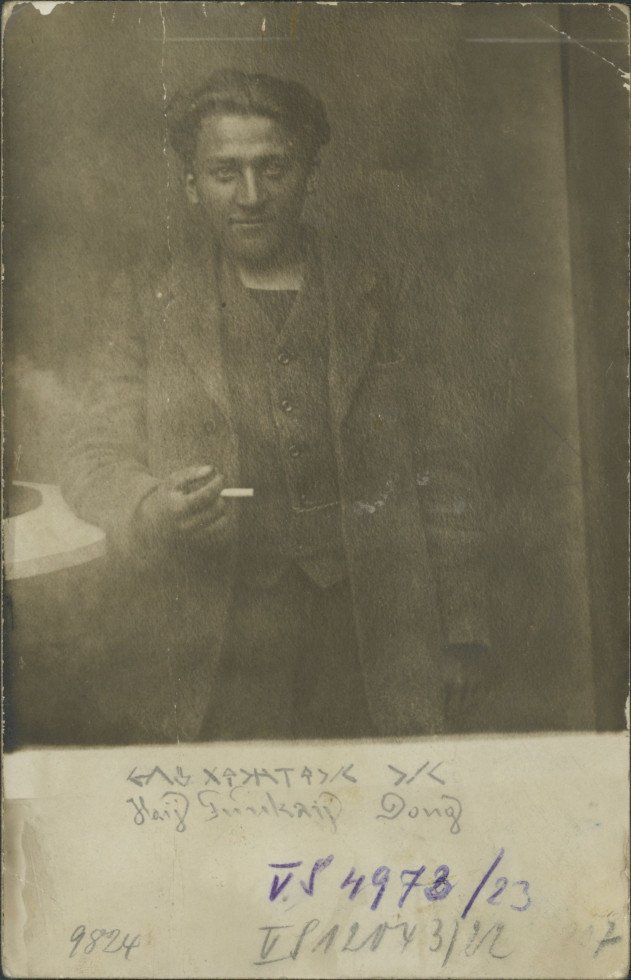

Confiscated documents of Wilhelm Palz that were moved around various offices when determining his right of residence, September 22, 1921-May 5, 1922. | Author Arhiv Republike Slovenije

»The Experience of a Stranger and a Nameless Person: on the Expulsion of Wilhelm Palz from Ljubljana

»Pre-file cannot be found. The matter is time-barred. a. a.« noted an official of the internal affairs department at the Great Župan of the Ljubljana Oblast on October 27, 1928, after six years of searching for the municipality of residence of the artist Wilhelm (Viljem) Palz or Haij Funkaij Dong. The Palz case, which started in 1922, is only one of many such cases of determining a person’s right of residence in a certain municipality for the purpose of his/her expulsion, preserved at the Archives of the Republic of Slovenia among the records of the Administrative Department of the Royal Ban’s Administration of the Drava Banovina.

Expulsion was a common practice used by local authorities to deal with various vagrants, the poor, beggars, Gypsies, prostitutes, and other unwanted subjects believed to cast a bad light on a certain town or municipality. The system of expulsing one to one’s municipality of residence was enacted in the Habsburg Monarchy in the 1870s and remained in force up until the monarchy’s disintegration and even after transitioning into the new state of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. In Slovenian territory, this duty was initially taken up by the Commission for Internal Affairs under The Provincial Government for Slovenia, later by the Internal Affairs Department at the Great Župan of the Ljubljana Oblast, and finally by the Administrative Department of the Royal Ban’s Administration of the Drava Banovina (throughout the entire period, they were subordinate to the Ministry of the Internal Affairs in Belgrade). After the change of government, this institute of expulsion also became a convenient means of removing German officials and other “foreigners” from the country, adhering to the principle “one’s own to one’s own”. But still, to carry out a successful and legitimate expulsion of an individual from a certain municipality, they first had to determine that individual’s right of residence (Heimatrecht).

Right of residence (Heimatrecht) also legally originated from the Habsburg rule and remained unchanged under the Yugoslav authorities. In general, the right of residence allowed an individual to live in a municipality without interference and to be provided for in case of him being unable to support himself. Individual received his right of residence by birth or marriage, or by applying for it at the municipal committee after having resided in the municipality continuously for four years.

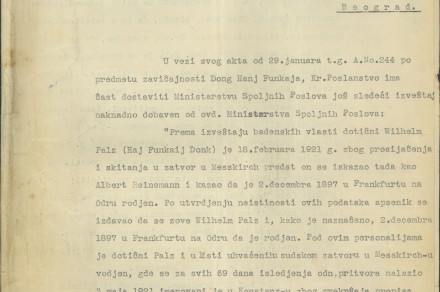

However, the latter was not the case with Wilhelm Palz, since this “German vagabond artist” had been roaming the streets of Ljubljana for only a couple of months before he was checked up by the General Police Directorate in Ljubljana in October 1922. The Directorate sent an inquiry into Palz’s municipality of residence to the Commission for Internal Affairs. The inquiry, together with the enclosed documents, was then sent to the Ministry of the Internal Affairs in Belgrade, which passed this task to the embassy of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes in Germany. Since the inquiry dragged on for months, the ministry in the meantime issued a decree, which unfortunately has not been preserved, but likely allowed Palz to stay in Ljubljana without any restrictions. In March 1924, Palz, using a pseudonym Haij Funkaij Dong, submitted an application for the extension of his visa to stay in the country, which the administrative department of the Great Župan of the Ljubljana Oblast forwarded to the ministry in Belgrade without hesitation “for political reasons”. The official of the administrative department had not noticed that the application was submitted by Wilhelm Palz, who at the time was in the process of being expulsed, but this observation did not escape the officials at the Belgrade ministry. In June that year, the ministry sent a letter, demanding to locate Palz and enclosing a report on determining his right of residence, which had apparently got stuck at the ministry in the middle of 1923 due to an incorrect file number. Whether the police in Ljubljana then managed to track down and expulse Palz is unclear, as the entire case eventually became time-barred.

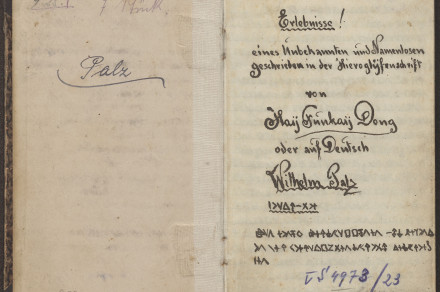

Still, the preserved documents tell an interesting story about the vagabond artist Wilhelm Palz or Haij Funkaij Dong, who had wandered through Western Germany and Austria before arriving to Ljubljana. Even German authorities were not able to find anything about his early years, apart from what he himself wrote. Claiming that he did not know his date and place of birth, he described himself as a mulatto and a pagan, who had been sold into slavery somewhere in the Indian continent (Hindustan) by bandits in 1912. He described his years as a slave in an imaginative first-person narrative about “some stranger and a nameless person”, set along the river Ganges and the Himalayan mountains. Parts of this story were even written in his own fabricated “hieroglyphic script”. In 1917, he claimed to have escaped from India across the Caucasus and Ukraine to Germany, where his documents, money and clothes were stolen. Despite the fact that this could have been only one of Palz’s false identities, the timeline of his escape from “slavery” suggests a possibility that he was one of German prisoners of war captured in the Great War in the tsarist Russia, who during battles on the Eastern Front experienced a mental breakdown, was captured and sent to the South Caucasus. Due to war trauma, he could have interpreted his captivity as slavery. Namely, the year 1917 coincides with the return of prisoners from the revolutionary Russia after the signed armistice with the Central Powers.

Despite everything, Wilhelm Palz was an intelligent person. He was well-educated, and the texts he wrote are almost completely free of any grammatical errors. He also had a vivid imagination and artistic flair. His handwriting was beautiful, adorned with various embellishments, as evident from his confiscated notebook. He used his “artistic” talents when wandering the towns in Germany in the early 1920s, where he was often arrested for begging and vagrancy. When arrested in Messkirch, he claimed his name was Albert Reinemann, born on December 2, 1897 in Frankfurt am Oder. When the authorities established that Albert Reinemann did not exist, he introduced himself as Wilhelm Palz. When arrested for the first time in Konstanz, he stated that he had been born in Beijing 25 years ago (hence the name Haij Funkaij Dong, which he also used to introduce himself). When arrested for the second time in Konstanz, he claimed to be married to Thea Hess from Frankfurt am Main. All the information Palz submitted to the police turned out to be false, prompting him to escape to the Austrian village Egg in Bregenzerwald, where he worked in a straw-hat factory for three months. From there he travelled to Ljubljana over the following months, where he once again came under the scrutiny of the authorities. Considering the fact that his location remained unknown in 1924, we can conclude that Palz again fled elsewhere.

Jernej Komac

- Naredba deželne vlade za Slovenijo, s katero se začasno ureja pristojnosti poverjeništva za notranje zadeve. In: Uradni list deželne vlade za Slovenijo, no. 24/1921, decree no. 115, pp. 100–101.

- Perovšek, Jurij: Slovenski prevrat: Položaj Slovencev v Državi Slovencev, Hrvatov in Srbov. Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2018.

- Stariha, Gorazd: »Z nobenim delom se ne pečajo, le z lažnivo beračijo!«: odgon kot institucija odvračanja nezaželenih. In: Zgodovina za vse 14 (2007), no. 1, pp. 37–76.